No Ghoulies, No Ghosties, But a Witch? Yep. Part 4

McMurray Family, Burnell Family (Click for Family Tree)

Mary (Bliss) Parsons and her husband Joseph Parsons remained in Boston for some time after her witchcraft trial in 1675, as Joseph owned warehouses there and had business in town. It would surely have been a good break from those who had accused Mary but lived so close by in Northampton. Although the jury that acquitted Mary was made up of ‘regular’ men from the Boston area, many in Northampton and elsewhere felt that having so many well-to-do members of society and friends of the Parsons family involved in the trial had ‘bought’ Mary her favorable results.

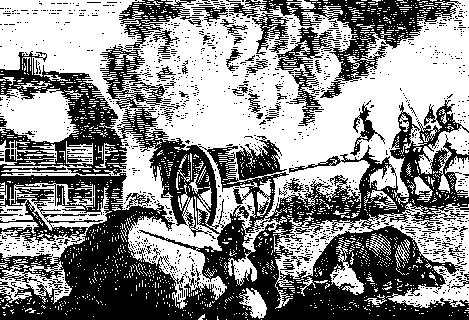

The son of Joseph and Mary, Ebenezer Parsons, had been the first white child born in Northampton on 1 May 1655. This was just before the son of Sarah (Lyman) Bridgman, one of Mary’s primary accusers, was born- yet another reason for Sarah to be envious of Mary. Ebenezer was only 20 years old when he marched off to Northfield after Indians had attacked a number of English settlements during King Philip’s War. (See note below.)

Ebenezer was killed on 8 September 1675 during the fight with the Indians per some recent sources; older historical sources state the date of his death as Thursday, Sept. 2, 1675. This being just after his mother Mary’s acquittal in her witchcraft trial, those who had worked to bring her to trial said,

“Behold, though human judges may be bought off, God’s vengeance neither turns aside nor slumbers.”

The neighbors assumed that the loss of her beloved son was punishment for Mary’s ‘pact with the devil.’

Despite the continued rumors, Mary and Joseph Parsons did return to their home and family in Northampton, likely before 1678/9.

Their story continues…

On 7 March 1679, another of our Burnell ancestors (not related to the Bliss or Parsons families), John Stebbins of Northampton, died suddenly and mysteriously. An examination of the body showed, “warmth and heate in his body that dead persons are not usual to have” and that his neck had the same flexibility of that of a living person, so rigor mortis had not completely set in. His body had “several hundred of spots” that seemed as if “they had been shott with small shott.” When these spots were scraped, there were holes under them. A second examination was reported to a court of inquest: he had bruises that had not been there during the previous examination, and “the body somewhat more cold yn before, his joints were more limber.”

John Stebbins owned a sawmill, and although some (now) think his death was caused by runaway logs hitting him, some of the townspeople back then thought his death was due to witchcraft.

How does this pertain to Mary (Bliss) Parsons? Well, we know that she had been accused of witchcraft more than once. Also, she was back in Northampton, thus near where John Stebbins died. But even more damning was the fact that the wife of the late John Stebbins was Abigail (Bartlett) Stebbins. Does that Bartlett maiden name sound familiar? Yep- Abigail was the sister of Samuel Bartlett, the husband/widower of Mary (Bridgman) Bartlett, that Mary had been accused of killing through witchcraft in the 1675 Boston trial. It was the death of Mary (Bridgman) Bartlett’s young sibling that caused the first case of slander, against her mother, Mary (Lyman) Bridgman, to be brought by Joseph Parsons in defense of his wife Mary. (Yes, we almost need a detailed roadmap- so many Marys, and same last names to untangle. Maybe we just need infographics rather than narrative posts??)

Samuel Bartlett seemed to be the community’s ‘witch finder’ and he brought in testimony to the inquest concerning the death of John Stebbins. There is no record existing today that Mary (Bliss) Parsons was accused of the death through witchcraft, but some historians believe she was the target of such rumors, especially with the bad feelings between her family and the Bartletts/Bridgmans continuing through the years.

The court of inquest rendered a verdict that did not directly charge anyone with witchcraft, but at least half of the twelve male jurors believed that witchcraft had been involved. Evidence was then sent to the Boston Court of Assistants, but unfortunately that information has not survived either. There was no further action taken, however.

They had had enough- Mary and Joseph moved their household back downriver to Springfield, Massachusetts in 1679 or 1680. Springfield had been attacked and burned during King Philip’s War, so maybe it was a sort of fresh start for them. Their son Samuel Parsons remained in the family home in Northampton.

Joseph Parsons, Sr., died in 1683 and Mary, like her mother, Margaret (Hullins) Bliss, began a long widowhood.

But it was not completely over.

Twenty-two years after Mary moved back to Springfield, Peletiah Glover, a prominent Springfield merchant who possessed much wealth, went to court in 1702 to indict the slave woman Betty Negro for “bad language striking his son Peletiah.” The 14-year old Peletiah testified to the court that the slave had claimed that his grandmother “had killed two persons over the river, and had killed Mrs. Pynchon and half-killed the Colonel, and that his mother was half a witch.”

Can you guess how this relates to our study of witchcraft in Springfield and Northampton, Massachusetts? Yep, it ‘relates’ because these people were relatives- Peletiah Jr.’s mother was Hannah (Parsons) Glover, the daughter of our Mary (Bliss) Parsons. So young Peletiah’s grandmother was Mary, a full-blooded witch per the assumptions of townspeople, and thus his mother was “half a witch.”

Mary was not taken to court for this- her friends and relatives likely helped her out in this respect. A man of great prominence in Northampton and one of the Justices of the Peace who presided over the case was one Joseph Parsons; he was also the son of Mary and Joseph (Sr.), thus also the elder Peletiah’s brother-in-law and uncle of the younger Peletiah. The other Justice was John Pynchon, a frequent business partner to Cornet Joseph Parsons (Sr.). John Pynchon had also testified for Mary years before in the slander trial and was involved in her witchcraft trial.

The slave Betty “owned it she had so said.” (Interestingly, one ‘Tom Negro’ testified against Betty Negro.)

The court record for 9 January 1702 states:

“We find her very culpable for her base tongue and words as aforesaid…We sentence said Betty to be well whipped on the naked body by the constable with ten lashes well laid on: which was performed accordingly by constable Thomas Bliss…”

The last name of Thomas Bliss who carried out the sentence is, of course, familiar too: the constable was the son of the brother of Mary’ (Bliss) Parsons, thus her nephew.

Mary died at about age 85 in 1712. She was unwell and confused enough that her sons Joseph and John Parsons took over her estate the year before she died.

◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊

Mary was lucky- six women were executed for witchcraft in Massachusetts even before the Salem witch trials of 1692, when 20 persons were executed (19 hanged, 1 pressed to death) and four died in prison while awaiting trial.

Witches could be a good community scapegoat for ills which could not yet be explained by science or disease, and claiming someone was a witch was sometimes the next step in an argument or long-standing feud. There are theories about ergot (a fungus) in the rye that was a dietary staple and could cause hallucinations and the ‘fits’ so often seen in victims of witchcraft. (The ergot would affect a smaller body, like that of a young girl, faster than that of an adult, possibly explaining why young women/girls were those primarily with ‘fits.’)

Sociologists have also postulated that witchcraft accusations take up the time of the people when they are in a lull with fighting enemies or the weather for survival, and act as a safety valve for human dissension.

Whatever our 21st century take is on witchcraft, it was a real fear for our ancestors- no matter if they were accused or accuser. The story of Mary (Bliss) Parsons illustrates that well.

Notes, Sources, and References:

- Also known as Metacom’s War, ‘King Philip’ was the English name of the warrior Metacom/Metacomet. King Philip’s War was between the English colonists who had some Native American allies, vs. the other natives of New England, mostly Wampanoags and Narragansetts. Within less than a year, the population of the colonies were decimated, including a loss of at least 10% of the men of fighting age. More than half of the towns were attacked with twelve burned to the ground, and the economy of the colonies was almost ruined with the loss of livestock, crops, and goods. Many English residents had been carried off by the natives and carried into Canada, sometimes sold as slaves. The war lasted from 1675-1678. England provided very little support for the colonists during the war, thus they banded together, resulting in a colonial identity separate from English subjects. This was just the first alienation of colonists that would result in a much bigger separation 100 years later. For more of this history see the very excellent book, Crucible of War: The Seven Years’ War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766 by Fred Anderson, Vintage, 2001, or his shorter version (293 pages vs. 912), The War That Made America: A Short History of the French and Indian War, Penguin, 2006. (A companion to the PBS documentary The War That Made America: The Story of the French and Indian War, 2006, available on DVD.)

- See resources in Part 3.

Please contact us if you would like higher resolution images. Click to enlarge images.

We would love to read your thoughts and comments about this post (see form below), and thank you for your time! All comments are moderated, however, due to the high intelligence and persistence of spammers/hackers who really should be putting their smarts to use for the public good instead of spamming our little blog.