No Ghoulies, No Ghosties, But a Witch? Yep. Part 1

McMurray Family, Burnell Family (Click for Family Tree)

Well, sort of.

Ghoulies and ghosties are fun Halloween fantasies, and witches would be too if there had not been real women- and some men too- who were accused of witchcraft in the very early years of our country, and around the world through the centuries. Some would be convicted and executed, as in the Salem, Massachusetts witch trials of 1691-2. However, the Salem hysteria was predated by even earlier accusations and trials in Britain’s American colonies- and in places where our ancestors lived.

In fact, if you are a McMurray or Burnell,

one of our ancestors was accused, and tried, as a witch.

Really.

(Did Grandma tell this family story?? Likely, she did not even know of it.)

And to make the story even better, apparently another family line was quite involved, but not in a good way. (New England was a small place in the 1600s.)

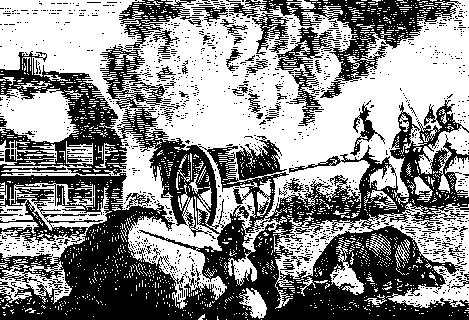

Mary Bliss was born in England about 1628, a time when witches and Satan populated the world in Puritan minds, and those of other religious persuasions as well. Surprisingly to us today, educated and literate people felt these entities were very real, and just waiting to harm them or their crops, livestock, homes, property, and family; for illiterate people, the fantastical was even more acceptable. Just imagine the darkness of New England in the winter, being in a small home with little light from handmade candles and the fireplace, possibly a woman alone with many children to protect while her husband was out hunting for days or traveling for trade. Add the damp cold and mist, the forest nearby with animals howling and prowling, plus Native Americans rustling about, and a Halloween setting was in place- but this occurred every day of the colonists’ lives. Fear of the physical and the spiritual reigned.

Mary Bliss’ family migrated from Olde England to New England when she was about eight. She married Joseph Parsons in Hartford, Connecticut, and then they moved to Springfield for several years and had a few children. As Northampton, Massachusetts began to be settled in 1654, Joseph and Mary Bliss Parsons moved their household out into the wilderness. Joseph was quite successful in both towns, and they had one of the nicer homes and better furniture than many of their neighbors. They eventually had eleven children who survived into adulthood- thus were more successful in myriad ways as compared to many of their neighbors.

Mary Bliss Parsons was apparently something of a contentious person- not unusual for the times in men, but as a woman, her haughty and strong mannerisms and ways of dealing with people caused problems, and engendered gossip. The family’s constant rise economically, socially, and politically made Mary the envy of some of her neighbors, and enemies to others. Joseph apparently was contentious as well, and very litigious- both traits common in successful businessmen, then as now.

One of their Northampton neighbors, Sarah (Lyman) Bridgman, accused Mary of causing the death of her two-week old son through the use of witchcraft. Sarah and her husband James Bridgman had followed a similar life-path as the Parsons had with their migrations, including being born in England, then migrating to Springfield, Massachusetts, and moving to Northampton, but after the Parsons family had moved there. James had not done as well as Joseph, however, and Sarah’s children frequently died young.

A feud seemed to have developed between the families, especially after an earlier incident in Springfield in which the Bridgman’s older son had been tending their cows in the swamp, when he received a ‘great blow to the head.’ He stumbled and injured his knee. The knee had been set but was painful and did not heal properly. One day the child screamed that Mary Parsons was pulling his leg off. He said he saw her on the shelf on the wall, and then she disappeared, with a black mouse following her. This could only be caused by supernatural evil, they thought, and Sarah spread malicious gossip about Mary around Springfield in those years. Once the Bridgmans moved to Northampton, the gossip continued, and escalated. Sarah Bridgman (and others) definitely claimed that Mary Parsons was a witch. Many felt that Mary’s witchcraft was how the family did so well for themselves.

To stop the rumors, Mary’s husband Joseph Parsons filed a lawsuit against Sarah Bridgman citing slander. (Women, of course, could not file a lawsuit at that time- their husband had to do any legal work needed.) Joseph and Mary were taking a risky path with the lawsuit, as it might draw greater than normal attention by the authorities if they felt the rumors were true, and Mary could end up having to defend herself from the accusation of witchcraft.

The court was held in Cambridge, Massachusetts, as the higher Magistrate’s Court was required to hear such serious accusations concerning witchcraft. Thirty-three depositions were taken from friends, family, and neighbors in October of 1656, with families from both Northampton and Springfield testifying. Sarah Bridgman told her story that in May two years earlier, as she was with her newborn in her home,

“having my child in my lap, there was something that gave a great blow on the door, and at very instant as I apprehended my child changed: and I thought with myself and told my girl I was afraid my child would die.’

Sarah claimed she saw “two women pass by the door with white clothes on their heads,” but her girl had seen no one. Sarah then knew her son would die soon because there was “wickedness in the place.” Her son was dead in just two weeks.

Others stated that the rumors were ‘truth,’ not slander, and returned to past ill words and unpleasant interactions with Mary. One neighbor related that Mary complained to her that the yarn she had spun for Mary had knots, as did the second batch she sent to replace it; the spinner related that other persons did not have the same problem with the yarn she had spun for them, so Mary’s witchcraft had likely caused the knots. Mary had asked this same neighbor to let their daughter work for her, but the rumors of witchcraft had already taken hold, and they refused; the daughter became ill shortly thereafter- again, the neighbor testified, evidence of witchcraft as retaliation. After an argument with Mary about missing yarn, the husband of the spinner found his cow “ready to die” and it did, within two weeks- of course that too would have been caused by Mary’s witchcraft, as revenge for the “discontented words passed” between them. “Hard thoughts and jealousies” abounded concerning Mary Parsons (with ‘jealousies’ at that time meaning accusations, not envy).

Incidents in Springfield from years before were also brought before the court, such as Mary in a ‘fit’ moving through water but not getting wet, Mary walking about at night, sometimes with an unknown woman (thought to be a spirit), or Mary being able to find the key her husband hid from her when he locked her in their house or cellar. (He also beat her in front of others, and their child. They had a stormy relationship.)

Other witnesses, more favorable to Mary, testified that Sarah Bridgman’s baby had been sickly since birth and that the cow died of “water in the belly” rather than some unnatural cause.

Numerous witnesses then recanted their testimony, stating that they had been induced by the Bridgmans to lie or that whatever incident they had related may have had natural causes. Mary was not above reproach in such evidence tampering matters either- she and her husband had influential friends who tried to suppress or alter testimony.

As proving Sarah’s slander was actually the point of the lawsuit, Mary’s mother, Margaret (Hullins) Bliss told the court that she had been told by Sarah Bridgman that “her daughter Parsons was suspected to be a witch.”

Thirty-seven persons in two communities were involved in the trial, with 15 families who lived in Northampton, and 7 from Springfield. It had taken an entire summer to gather all the evidence- it was quite a big event in the two little frontier towns on the edge of wilderness.

That fall the court ruled that Sarah Bridgman had indeed committed slander. Repentance was important to a Puritan community, and Sarah Bridgman was given the choice of a public apology to be done in both Northampton and Springfield, or pay a fine that they really could not afford. The Bridgmans decided to pay the fine instead of backing down, probably to avoid the humiliation.

The trial was over, but suspicions and the troubles of Mary Parsons were not.

To be continued…

Notes, Sources, and References:

- We have the ‘Lyman’ and ‘Bartlett’ accuser’s surnames in the family as well, but this author is just beginning to research those relationships.

- There is quite a lot of information online about Mary Bliss Parsons- with 11 children surviving to adulthood, she has a LOT of descendants. Not all is fully accurate, so reading more scholarly journals and genealogical and other books concerning Mary will be the best sources. Following are just a few of the very many sources consulted for this blog post and those upcoming about Mary.

- A Place Called Paradise. Culture and Community in Northampton, Massachusetts 1654-2004. Edited by Kerry W. Buckley, Historic Northampton Museum & Education Center/ University of Massachusetts Press. Chapter 3 is “Hard Thoughts and Jealousies” by John Putnam Demos, from his excellent, very comprehensive book Entertaining Satan: Witchcraft and the Culture of Early New England, New York, 1982.

- The History of Northampton, Massachusetts from its settlement in 1654,

by Trumbull, James Russell, (1825-1899); Pomeroy, Seth, (1706-1777), 1898. (Seth Pomeroy is a very distant cousin too.) Available on Internet Archive- https://archive.org/stream/historyofnortham00trum#page/n11/mode/2up

- Cornet Joseph Parsons one of the founders of Springfield and Northampton, Massachusetts, by Henry M. Burt, Garden City, 1898. –https://archive.org/stream/cornetjosephpar00parsgoog#page/n10/mode/2up

- Parsons Family. Descendants of Cornet Joseph Parsons Springfield 1636- Northampton 1655, by Henry Parsons, New Haven, 1912.

(Journals will be added with Part 2.)

Please contact us if you would like higher resolution images. Click to enlarge images.

We would love to read your thoughts and comments about this post (see form below), and thank you for your time! All comments are moderated, however, due to the high intelligence and persistence of spammers/hackers who really should be putting their smarts to use for the public good instead of spamming our little blog.

![Winter in New York- similar to that in Massachusetts. William Rickarby Miller [No restrictions or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://heritageramblings.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/443px-Brooklyn_Museum_-_Winter_Scene_Pleasant_Valley_New_York_-_William_Rickarby_Miller_wikimedia_public-domain-370x500.jpg)