“Waste Philosophy” by Rev. Edward B. Payne, 1892: The Poem

McMurray Family, Payne Family (Click for Family Tree)

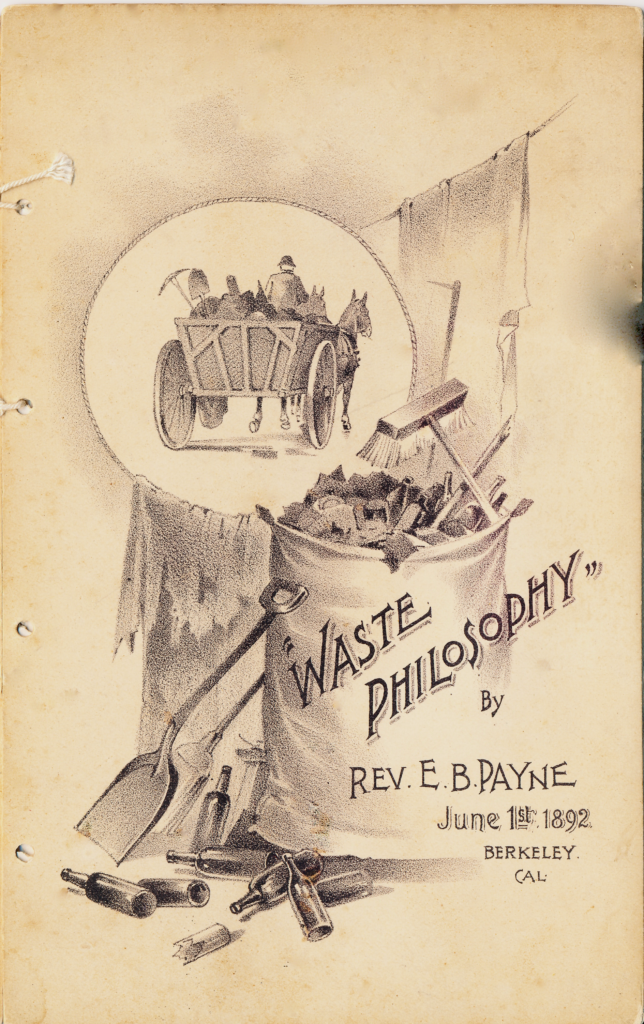

“Waste Philosophy” is a small printed booklet of a poem written by Edward B. Payne in 1892. The booklet is just 6-7/8″ high and 4-3/8″ wide, with 2 cardstock covers and 6 inner pages, 5 of which are printed double-sided. There is no note of the printer, but it appears to have been printed on a press. There are four holes punched through the booklet on the left, with pieces of string in two of the holes, although the string seems to be much more recent than what might have been there in 1892.

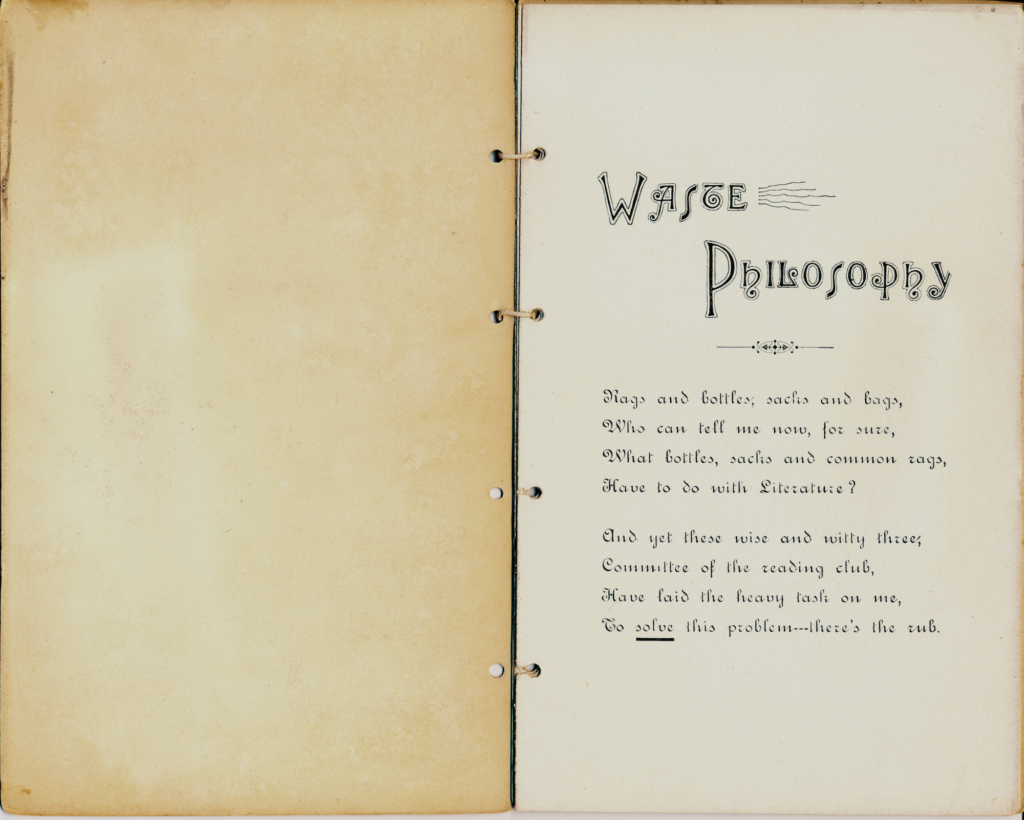

The first page gives us an introduction- why is the author on a quest to determine how rags and bottles, sacks and bags, are connected to literature?

Words are underlined throughout the poem, but it appears they are only in the family copy. Edward’s daughter, Lynette, may have made them using a ruler and pen. We have not yet found a correlation between the words underlined. (Any ideas?)

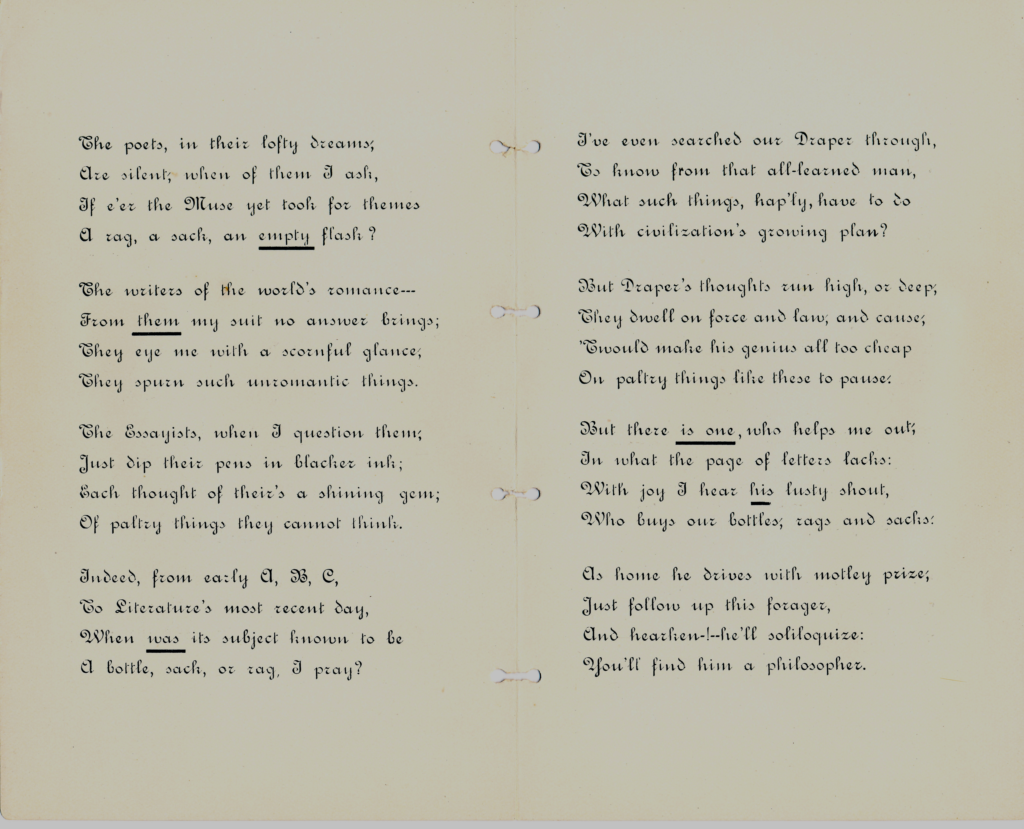

In the poem, Edward asks poets, writers, and essayists to help him answer the question he has been given. Without satisfactory answers from any of these persons, he moves on to the “draper”- a person who sells cloth, clothing, and dry goods. The local Draper apparently is quite a learned man, but unfortunately he does not have an answer to the question either.

Without an answer, Edward thinks of one who might concern himself with smaller things than the poets, writers, and essayists of literature would bother. He hears the cry of the local ‘Forager’ who buys bottles rags, and sacks from persons throughout the area. He already knows the Forager is a philosopher, something that most would not assume of a person who is of the ‘lower class’ of society. Edward himself was a Christian Socialist and he was also educated as a minister at a very liberal college, Oberlin, which was instrumental in the Abolitionist movement and helping the common person, no matter the color. Edward spent much of his life lovingly working to help people ‘lift themselves up by their bootstraps’- working with them to better their lot in life, rather than just giving them handouts, as many think of Socialists these days.

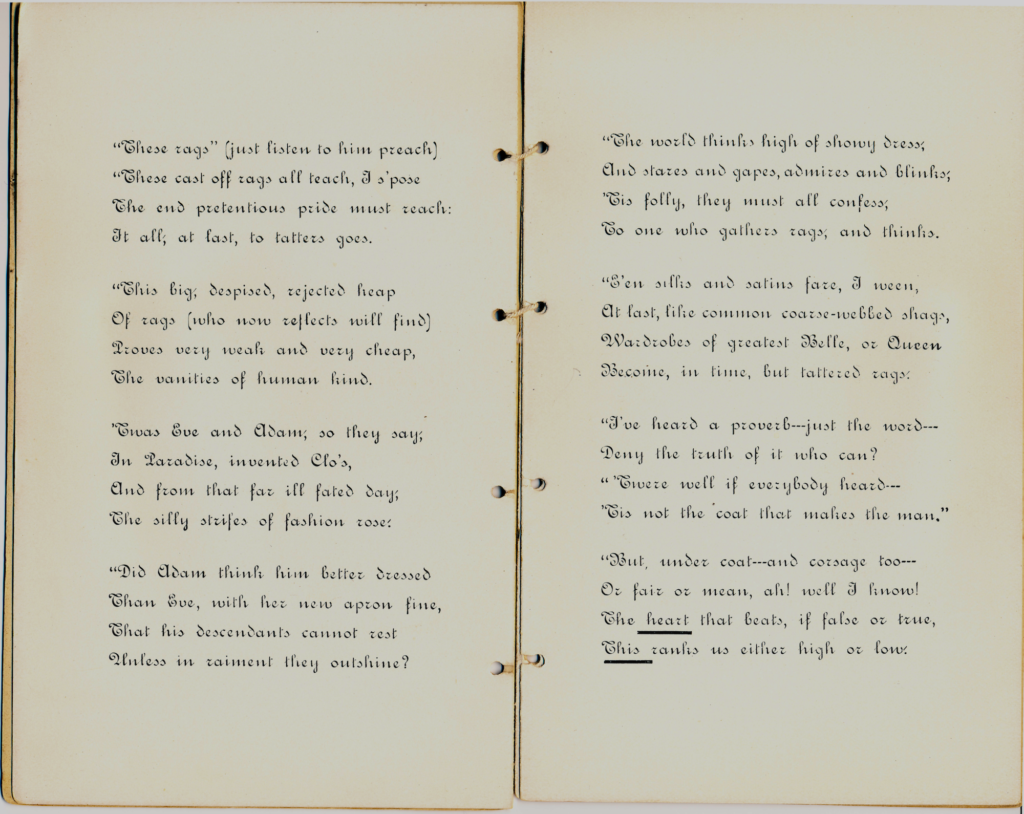

It is interesting that EB (as Edward B. Payne is lovingly known in our household after many years of research) uses the word “preach” when speaking of the reply the Forager has to the central question this poem asks. Edward himself was an eloquent preacher, as stated by his parishioners and colleagues, newspaper writers, and friends. His father-in-law was a very effective lay preacher, so EB knew that a divinity degree was not required for one to have important things to say. The word is also a clue that there are some big ideas that will come of the Forager’s comments- ones that could give new meaning to a human life.

Of course, “Preach” also rhymes well with ‘teach’ in this stanza- that’s important in an ABAB rhyme pattern.

The Forager describes the rags he finds as sometimes coming from the finest clothes. He states that a ‘coat’ for men and ‘corsage’ for women don’t make the person finer- it is “The heart that beats, if false or true” that “ranks us high or low.”

The Forager moves on to describe the bottles he collects. He knows that some are innocent, like perfume bottles, but others can be poison, in many senses of that word. In the 1890s, there was no Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to ensure the safety of what we consumed. Medicines were adulterated with other drugs or cut with chemicals that were a poison, or there were ingredients that so diluted the original drug that it was ineffective; oftentimes the product just did not work but the advertising or salesmanship was so impressive that people bought it anyway. Other drugs were powerful narcotics that persons would become addicted to easily, and for life. Sadly many died due to the cure, rather than the disease.

Apothecaries/druggists also sold alcohol at times without having a license to sell it, as a saloon would have needed to purchase from the city. Alcohol for ‘medicinal use’ was common, even before prohibition in the 1920s, and was often given to women who had physical complaints. EB was an advocate of the temperance movement, as he had seen the pain of alcohol addiction many times in his professional life. As a young minister in the tenements of Chicago he worked with D. L. Moody in the poor immigrant communities, and he also ministered in mill towns in New England. In fact, he gave up his ministry at a wealthier New England church, in order to minister to those who needed him more. He and his wife also sheltered in their home a young woman who most likely had been escaping from domestic abuse by her husband, and EB testified at a trial concerned with her disappearance. While we do not know if excessive alcohol use was involved, it is well known that alcohol consumption was very high in these poor communities with little hope of a better life. Edward worked to help decrease the use of “bottled sin” in communities, and reform the laws of cities and our nation.

The Forager has been at his job- and life- long enough to be able to identify what spirit was in each bottle at one time. It is ironic that he laments the fact that there isn’t a drop left for him, despite what he knows to be true of the dangers of alcohol.

The Forager continues to preach that he has had bottles from some of the pillars of the community, and he wants Edward to “keep still’s a mouse” with what he tells. Even the parson had empty bottles, although they might not have been his, since he had not lived there very long- or had he drunk the contents quickly?

Bags the Forager gathers have stories to tell as well. He uses the bag as a personality metaphor- a bragging person is a “bag o’ wind.”

A woman who was a gossip and tattler ironically provided a “wide-mouthed sack” and the word “tell” is in the name he calls her. A greedy, cheap man provided only small bags, and the Forager states that when that man is dead, the worms will “find his heart too hard to eat.”

The Forager summarizes his “Waste Philosophy”: we can find wisdom, morals, and lessons in the humblest of objects, if we but look for them.

Edward finishes his poem by an appreciation to the committee that charged him with “a grievous task” of finding out how literature is related to “bottles and rags, bags and sacks.” He has found that those simple objects tell us much about the human condition, and give us guidance in our own lives. While he doesn’t say it directly, this is exactly what good literature- and good poetry- does for its readers. The Reverend then offers a blessing for the committee concerning their bottles and eventual rags. He ends his poem with another blessing that is a play on the word “sack”- that St. Peter will “not give them the sack” when they get to the Pearly Gates.

Spoken like a true- and clever- preacher.

Notes, Sources, and References:

- “Waste Philosophy” by Rev. Edward B. Payne, 1892, Berkeley, California. Scans are from a family copy that was lovingly given to the author.

- References to the various episodes of Edward B. Payne’s life related in this article can be provided if desired. They are not being added here today because of the time involved- it is more important that the time be used to sew masks for those in need during this pandemic. While a meticulous researcher and logical debater, I feel EB would concur on this better use of time.

Click to enlarge any image. Please contact us if you would like an image in higher resolution.

We would love to read your thoughts and comments about this post (see form below), and thank you for your time! All comments are moderated, however, due to the high intelligence and persistence of spammers/hackers who really should be putting their smarts to use for the public good instead of spamming our little blog.