Caspar Bierbauer- A Revolutionary War Ancestor to be Celebrated on Veteran’s Day

HELBLING Family, BEERBOWER Family (Click for Family Tree)

Genealogy always has components of serendipity, even when one really tries to stick to a research or writing plan. This is what happened recently, when a question about membership in the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) led to some new information and connections within our Beerbower ancestors.

The DAR has made documentation of our Revolutionary War veterans a top priority, and they also work with schools and other groups to promote history and patriotism. Women who are interested in joining DAR must research and prove relationships to an ancestor who,

“with unfailing loyalty, rendered material aid to the cause of Independence”

DAR provides some of their genealogical materials to non-members researching their family history. (Thank you, DAR!)

Today is Veterans Day in the United States, when we honor all those who have served our country to create and preserve our democracy. This story includes four ties to Veterans Day: Elsie Janis, a cousin who became a DAR member and served our country in war though not as a member of the military; her British fiancé Basil Hallam, who died while serving in World War I; her husband Gilbert Wilson, who served in the Army in World War II; and the ancestor to Elsie and to the St. Louis Helbling branch and various Beerbowers, Caspar Beerbower/Bierbrauer, who served in the militia during the Revolutionary War. Elsie joined the DAR on Casper Bierbower’s record.

Because this story grew the more it was researched, this will need to be a multi-post narrative. The connections are wonderful through the years, however, so we hope you will enjoy reading. We will start with one of the persons who made “us” possible, our direct ancestor Caspar Bierbrauer (Bierbrauer, Beerbower, Bierbower, Beerbrower, etc.).

It is believed that Casper Bierbauer was born in 1736, possibly in Westerwald, Schaumburg, Niedersachsen, Germany, but this needs more research to verify. Also needing more research is exactly when he came to the American colonies, but a number of sources state it was 1752, when he was 16. He came with his father, Johann Jacob Bierbrauer (1705-1760), and possibly his mother Annae Christiannae Sonderhausen (although we do not know for sure if she made the voyage, since so little was recorded of women’s lives). His siblings made the trip as well. They were a part of the largest wave of German immigration to Pennsylvania, from about 1749-1754. Constant wars in the German principalities, a need there for young men for military service (Casper was about that age), and reports of America being a paradise were some of the reasons that whole families immigrated to the colonies.

When Casper was about 29 he married Elizabeth Ashenfelter (~1740-1821). They may have lived in Chester County, Pennsylvania in the 1760s and 1770s, as a Casper Bierbower witnessed a will there on September 29, 1766, and another record states a Casper Bierbower had 100 acres, 1 horse, and 1 head of cattle in the county in 1770. There are also records for Chester County with a Casper Beerbower (with various creative spellings) being taxed there in Pikeland in 1762, 1764, 1765, and 1766; in E. Whiteland in 1767 and 1768, and 1771 in Vincent, all in Chester County.

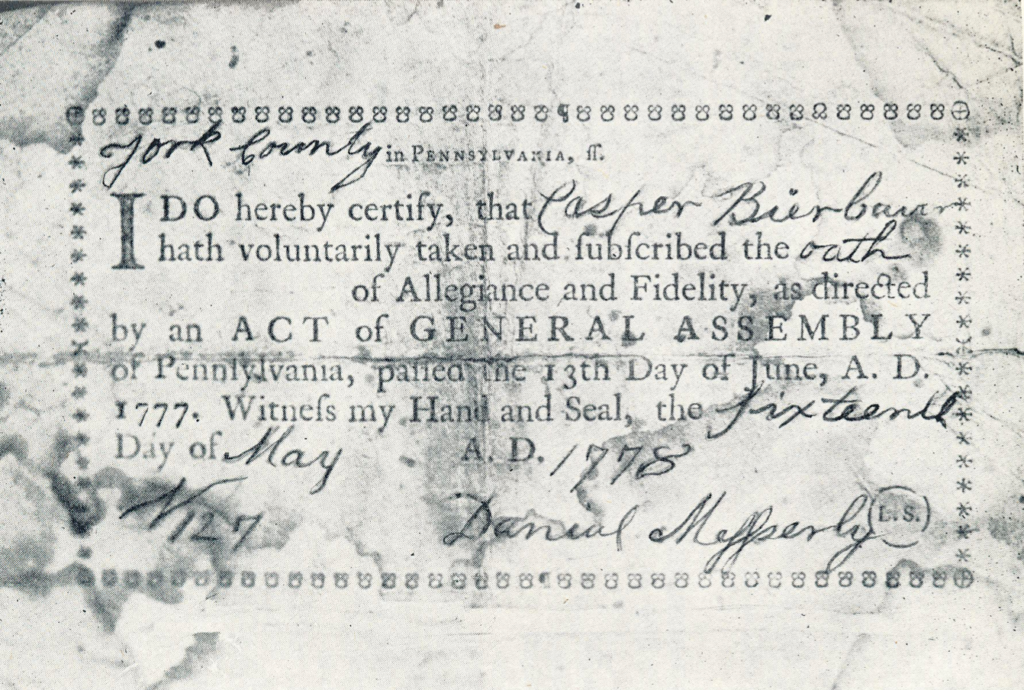

The Revolutionary War started in 1775 when Casper was 39, and continued through 1783. Casper signed the Pennsylvania Commonwealth’s ‘Oath of Allegiance and Fidelity’ on May 16, 1778, declaring his loyalty to the revolution, rather than to the king. He may have signed this eagerly, but would have known that what he was doing would be considered an act of treason by the king, if the rebels lost.

Casper signed that Oath in York County, Pennsylvania, so he and Elizabeth were living there by that date. He also paid tax in York’s Dover Township in 1780, and again in 1781 and 1783.

In May of 1779, as the Revolution raged on, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania required:

” a true and exact list of the names and surnames of each and every male white person usually inhabiting or residing within your Township, between the ages of Eighteen and fifty-three years, Capable of bearing arms.”

Certain persons were exempted from the list, including delegates in Congress or members of the Executive Council, faculty of colleges, Supreme Court judges, Ministers of the Gospel, and purchased servants (white, Indian, or black). (Possibly half of German immigrants came as indentured servants, or ‘redemptioners’ who could not afford passage so had to work off the cost in service, often with cruel masters.)

Male farmers, craftsmen, merchants, and others from the towns and sparse rural areas of the county were thus required to serve the Revolutionary cause when needed. Older citizens, like Casper Beerbower, could perform duties that freed up the younger for the more strenuous marching and battles.

At age 45, on December 8, 1781, Casper’s enlistment as a Private began in Captain John McMaster’s Company of the York militia. “Casper Beerbrower” was listed on John McMaster’s payroll from this date until February 8th, 1782.

The York Militia was stationed at Camp Security, an American camp for prisoners-of-war, from July 1781-May 1782. After Casper’s arrival, it was recorded in John McMaster’s log:

” Camp Security, 24th, Dec., 1781.

This is to certify that Casper Bierbower of the 7th Class of York County Militia hath put up his part of the Stockade and is hereby discharged.

Jno. McMaster, Capt.”

While much safer than being on the battlefield or a large camp filled with diseases like smallpox, Casper’s work was still hard labor. Logs would be felled, the ends shaped to a point, and a hand-dug trench was created around the camp. The logs would then need to be raised, with the pointed end up, and fitted tightly side-by-side. Then the men would have backfilled the trench, tamping the earth down to hold the logs in place. Gates, platforms near the top for observation and shooting, etc., would have also needed to be built.

Camp Security was one of many prisoner camps that were located in Pennsylvania. (A McMurray ancestor, Henry Horn, was a Hessian soldier captured at Trenton and taken to Lancaster, Pennsylvania.) Camp Security was built in the summer of 1781 on a 280 acre farm that had been confiscated. A stockade as well as living quarters were erected by the militia. British General Burgoyne’s troops, captured at Saratoga, New York, in 1777, had originally been housed in Maryland or Virginia. When battles moved closer to those areas, the prisoners were moved- in 1781, to Camp Security in York County.

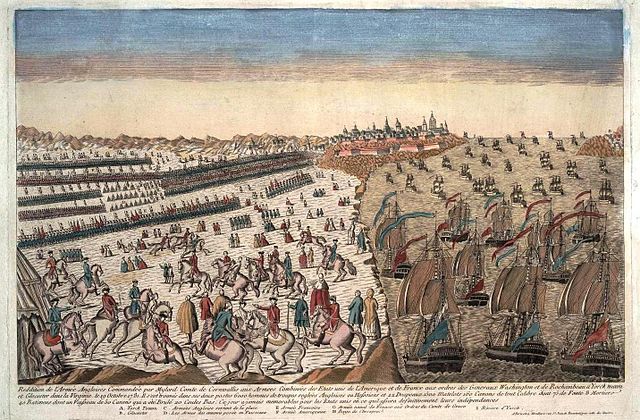

George Washington’s decisive Seige of Yorktown, with the assistance of French troops, began September 28, 1781. More than two weeks later, on October 19th, General Lord Charles Cornwallis and more than 7,000 of his troops surrendered. Cornwallis, however, was quite ungentlemanly and refused to attend the surrender ceremony. He may have realized that with this battle, the Americans had likely gained their independence from Britain.

The Americans had a new problem though- they had thousands of British prisoners to house. (Officers went free after parole.)

Note the dates- Casper helped build the stockade in December of 1781, so it was likely they were adding to the size of the camp to house the new Yorktown prisoners. The Burgoyne troops were still at Camp Security, but the new prisoners, privates and non-commissioned officers, were moved to Camp Security in the early months of 1782; the York Militia, Casper’s friends and neighbors, acted as guards for much of that year. Some of the more trust-worthy prisoners, such as officers and their families, lived in huts in a small village nearby. Many prisoners received passes to work locally for farmers and merchants, which helped to provide needed articles of clothing, bedding, and even food, and aided the locals since much of their population was off fighting the war. The troops of Cornwallis were a much higher escape risk than the Burgoyne prisoners,, so the new men were confined to the stockade. Estimates of the total number of prisoners varies, but it may have been around 3,000 in York County alone.

Like in so many crowded camps, a wave of fever ran through, killing many inhabitants. Once the war was over in spring of 1783, British prisoners returned to their homeland or were given land in Canada (by the British) for their service. The stockade and Camp Security was abandoned, but is now an archaeological and historical site.

And our ancestor Casper Bierbower? After “render[ing] material aid to the cause of Independence” at Camp Security, he and Elizabeth continued to reside in York County, Pennsylvania. They were enumerated in the first census of the United States, in 1790, with one male over 16 (presumably Casper), and 1 under 16, which could be Casper Bierbower Jr. or their youngest son, John Bierbower; three females lived in the household as well. Tax records suggest the family farmed, although we do not know if they owned the land, as one record over these years stated it was rented.

For the 1800 US Federal census, Casper and Elizabeth (likely) are found in Warrington, York County, Pennsylvania. Casper would have been 64 that year, Elizabeth 60, with their children grown and on their own. We can infer this since they were the only people listed in the household in 1800, both over 45 years of age.

Elizabeth died July 16th, 1821 in Warrington, York County, Pennsylvania per some sources but we have not found any reliable record for that date nor place. Casper, and possibly Elizabeth, may have moved after 1800 as we do not find them again in York County, Pennsylvania. Their sons Henry Bierbower and Casper Bierbower, Jr. lived in Washington County, Maryland, so a move there would be logical as the couple aged. On October 28th, 1820, a man listed as “Casper Beerbrougher” was listed in the 1820 US Federal Census for Hancock, Washington County, Maryland. There is one male listed as 26-45 years old, and one listed as older than 45; this could be Casper Jr., who would have been 38 that year, and Casper Sr., who would have been 84. There is no woman listed as being over 45 years old, so this suggests that Elizabeth had actually died by that date, not the year later, in 1821. There are young children in this household of nine, so this could be an instance when Casper as a widower was being cared for in his old age by his son, daughter-in-law, and his grandchildren. Casper died sometime in 1822.

We thank Casper for his service to our democracy.

Next: Elsie Janis, two of the men in her life, and her service during wartime.

Notes, Sources, and References:

- “German Settlement in Pennsylvania An Overview,” Pennsylvania Historical Society, https://hsp.org/sites/default/files/legacy_files/migrated/germanstudentreading.pdf

- DAR database for Casper Bierbower– https://services.dar.org/public/dar_research/search_adb/default.cfm

-

House of Bierbauer: Two Hundred Years of Family History, 1742-1942, compiled by James Culver Bierbower and Charles William Beerbower, 1942.

-

John McMaster’s payroll, as transcribed in Pennsylvania Archives, Sixth Series, Volume II, page 650. https://www.campsecurity.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/camp-security-listing.pdf

- Discharge of Casper Bierbower– Pennsylvania Archives, Sixth Series, Volume II, page 730.

- Some Camp Security links–

https://yorkblog.com/universal/new-camp-security-booklet-is-available-for-students-and-teachers/

https://yorkblog.com/universal/how-many-revolutionary-war-pri/ - Siege of Yorktown– https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siege_of_Yorktown_(1781)

- See Wikimedia for key to Yorktown surrender image– https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Reddition_armee_anglaise_a_Yorktown_1781_avec_blocus_naval.jpg

Click to enlarge any image. Please contact us if you would like an image in higher resolution.

We would love to read your thoughts and comments about this post (see form below), and thank you for your time! All comments are moderated, however, due to the high intelligence and persistence of spammers/hackers who really should be putting their smarts to use for the public good instead of spamming our little blog.