Thankful Thursday: Gittel Broida and the “German Titanic”

Broida Family (Click for Family Tree)

Very early in the morning of 19 January 1883, off the German Island of Borkum in the North Sea, the weather began to turn for the worse and very dense fog set in. The steamship SS Cimbria had left the day before in fairly clear weather from Hamburg, Germany, and had its usual crew of 120 (or 91 crew members, depending on source) plus 402 passengers, many of whom, like Sarah Gitel Frank (later Broida) just eighteen months before, were emmigrants to the United States. The emmigrants were from Russia, Prussia, Hungary, and Austria, plus there were French sailors headed to Le Havre, France (another common port of departure) and a group of Chippewa Indians who had performed exhibitions in Europe. There were 243 male passengers, 72 women, and 87 children on board the ship when it departed.

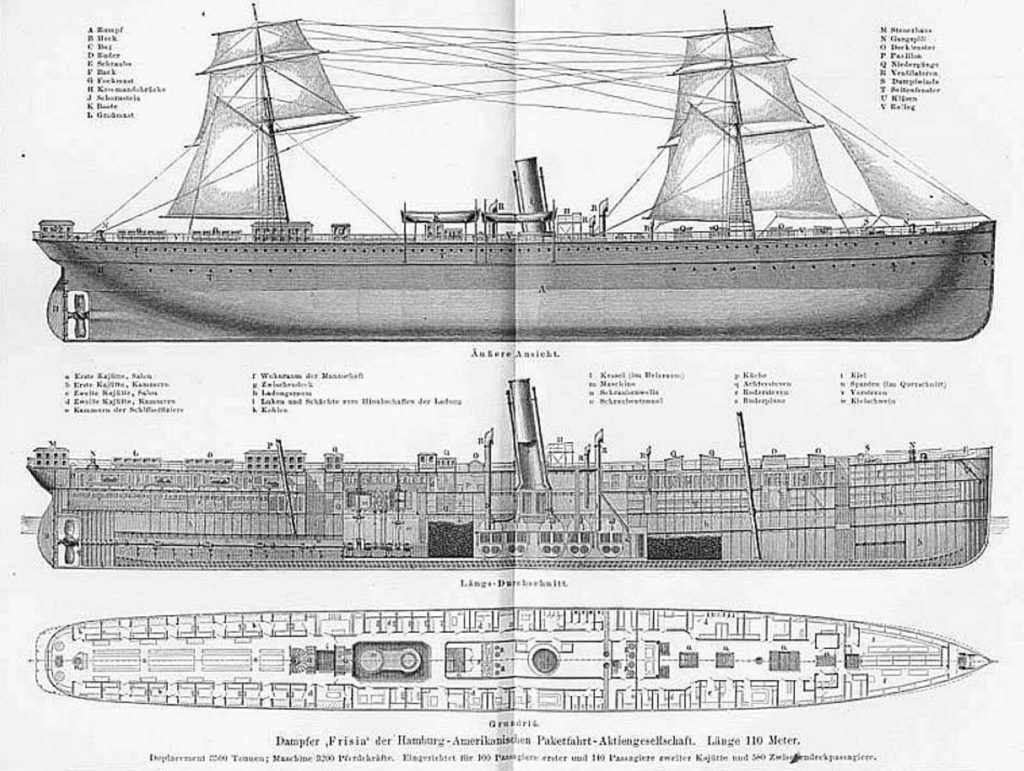

The SS Cimbria was built by Caird & Co. in Greenock, Scotland, in 1867 for the Hamburg America Line (now Hapag-Lloyd- you have probably seen their shipping containers on the back of an 18-wheeler). The ship was a 340 ft. steamer, about 40 ft. across the beam, built of iron and weighing 3,037 gross tons. With five boilers to create the steam to power her with a 600 horsepower engine, the two-cylinders drove one screw; gases were exhausted out the large funnel near the center of the ship. As did many of the steamers built in the 1860s, she also had two sailing masts to take advantage of the strong winds of the North Sea and Atlantic Ocean.

The ship could accommodate 58 first-class passengers, 120 second-class, and 500 third-class or “steerage,” – the latter most likely where the poor emmigrants lived on board.

As the fog grew thicker past the small town of Cuxhaven on the north German shore near where the Elbe River meets the North Sea, the experienced captain of the Cimbria became concerned and about midnight ordered that the speed of the passenger ship be decreased. As the passengers and off-duty crew slept, two hours later the siren of an approaching steamship was heard, but it was challenging to determine where it was with the muffled sound caused by the fog. A lookout then noted a faint green light in the dense fog. This green light showed a ship’s position to others, and belonged to the smaller British ship Sultan, which was carrying coal.

Once seen, the two ships were only about 150 ft apart.

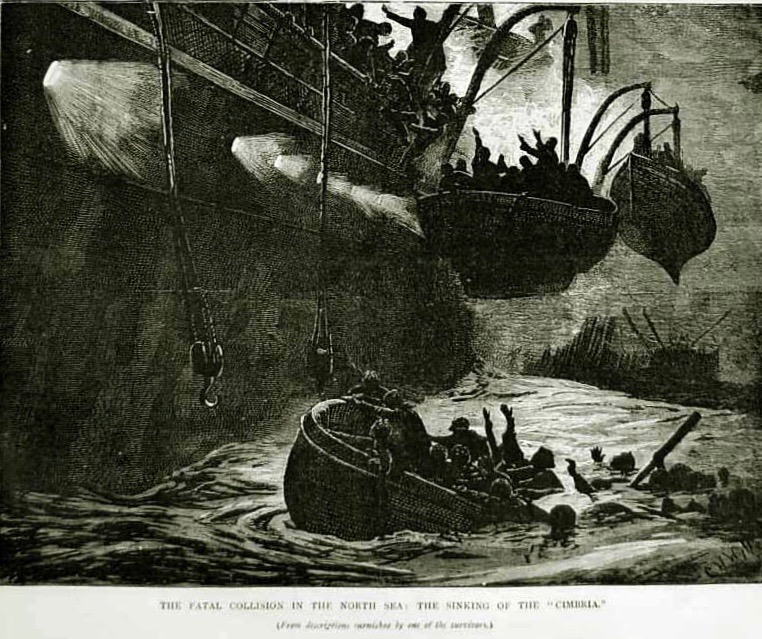

But it was too late- ships that size are not agile in water, and as the two ships loomed out of the fog, the captains panicked. To make it even worse, they did the absolutely wrong thing- they turned toward each other. Within moments the Sultan‘s bow struck the port side of the Cimbria, and a deep gash alongside the foremast that extended below the water line allowed many thousands of gallons of cold seawater to flood the Cimbria. The Sultan reversed itself using full power, but when it backed away, it also pulled off large iron side panels of the Cimbria, worsening the flood into the hold of the ship.

By this time the passengers would have been awakened and panic resulted. The Cimbria had begun to list, making it harder to escape from below decks, and as it was taking on water so quickly, the ship was sinking fast. The crew remained focused and were able to lower three (some sources state seven) lifeboats in the short time they had. Sadly, one of the boats was overcrowded and capsized, but others were able to escape the whirlpool and suction forming as the ship sank.

The Cimbria sank in just fifteen minutes. Fifteen.

The masts of the steamship thankfully remained upright and out of the water for many hours so passengers clung to the shrouds of the masts. One lifeboat had capsized soon after leaving the Cimbria, losing many passengers to the deep, but seventeen were able to get to a mast and hold on for over ten hours- they nearly froze to death (remember, it was winter in the North Sea!) before they were rescued by the German vessel Diamant. Before sinking the crew had cut off the spars of the mast and flung them into the water so that people could cling to them, although the cold water would not have allowed the survivors to live long. Lifeboats held thirty-nine who were rescued by the ship Theta two days later and nine persons landed their lifeboat safely at Borkum. Reports vary from a total of 65-133 persons saved.

None were rescued by the crew of the Sultan, however. The Sultan’s captain had steamed off, ignoring the screams for help from the Cimbria, the lifeboats, and the people in the icy cold, winter waters of the North Sea. He reported that he had feared he would lose his own lifeboats in the fog if they had been lowered. The captain later stated, in the Maritime Court inquiry, that he thought his ship had been damaged more than the ship he rammed in the side with his pointed bow. (There are varying accounts that state there may have been more than one collision between the ships.) The Sultan’s captain also stated that the Cimbria had not used their horn in the fog even though he had, and, at one point, stated he waited at the scene five hours but heard nothing so returned to Hamburg, furious that the Cimbria had not provided aid to his ship. When he returned to port, he learned the sorrowful fate of the Cimbria.

The Sultan’s captain was somewhat vindicated when it was determined that his ship did have a large hole forward. Had his ship taken on only one more foot of water, it too probably would have foundered in the cold North Sea.

More than 389-430 souls were lost that night from the SS Cimbria, making it the largest (known) maritime disaster until the loss of the Titanic in 1912. The Cimbria is still Germany’s largest loss of life from a ship disaster.

We can only imagine the reactions of Sarah Gittel (Frank) Broida and her family when they heard the news of the sinking of the SS Cimbria. She had wisely traveled not during the cold, stormy months of winter on the North Sea. Despite that, the fear of the ship sinking was always a reality preceding and during the trip. Knowing that she had immigrated just a year and a half before her ship went down must have been chilling.

Notes, Sources, and References:

- Websites and news articles vary in the number lifeboats that got away and number of souls lost and rescued.

- “Loss of the Cimbria,” Los Angeles Daily Herald, Vol. 18, No. 132, Page 1, Column 2, 24 January 1883. The news from the disaster is somewhat contradictory.– https://cdnc.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/cdnc?a=d&d=LAH18830124.2.3

- This website has 3 pages on The Cimbria, but you will likely need to use the search box at the bottom to get to each– http://www.gegoux.com. And yes, it is a page about an artist, mostly, but The Cimbria is included because he too traveled aboard the steamship around 1881.

- A very talented person built a beautiful model of the SS Cimbria, and documented the facts about the ship as well as the process of creating the model– http://www.shipmodell.com/index_files/SHIPMODELL_SS_CIMBRIA.htm

- Haag-Lloyd website, SS Cimbria page, including information about salvage efforts that include wine bottles, ivory, and the ship’s bell (which Gitel Frank would have heard on her voyage)– https://www.hapag-lloyd.com/en/news-insights/insights/2017/06/_cimbria_-catastrophe–the-story-of-the-german-titanic-began-150.html

- One of the sources consulted by some of these websites was “Know Your Ships” Tenth Edition, 1968, Thomas Manse, Publisher.

Click to enlarge any image. Please contact us if you would like an image in higher resolution.

We would love to read your thoughts and comments about this post (see form below), and thank you for your time! All comments are moderated, however, due to the high intelligence and persistence of spammers/hackers who really should be putting their smarts to use for the public good instead of spamming our little blog.Original content copyright 2013-2018 by Heritage Ramblings Blog and pmm.

Family history is meant to be shared, but the original content of this site may NOT be used for any commercial purposes unless explicit written permission is received from both the blog owner and author. Blogs or websites with ads and/or any income-generating components are included under “commercial purposes,” as are the large genealogy database websites. Sites that republish original HeritageRamblings.net content as their own are in violation of copyright as well, and use of full content is not permitted. Descendants and researchers MAY download images and posts to share with their families, and use the information on their family trees or in family history books with a small number of reprints. Please make sure to credit and cite the information properly. Please contact us if you have any questions about copyright or use of our blog material.SaveSave

SaveSave