Wedding Wednesday: Mary Parsons and Ebenezer Bridgman

McMurray Family, Burnell Family (Click for Family Tree)

The Romeo & Juliet story has been passed down through the centuries in various forms, and has been lived in real life by many. Think back, if you will, to four previous posts detailing the bitter feud between the families of Mary (Bliss) Parsons and Sarah (Lyman) Bridgman. Sarah accused Mary of being a witch as far back as the 1650s. The feud had gone on even before that time, but could there be two people in the future who would mend those fences, as Romeo and Juliet did for the Montagues and Capulets??

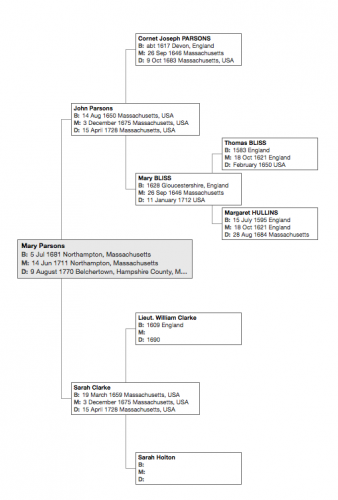

One of the children of Mary (Bliss) Parsons- the accused witch- and her husband Cornet Joseph Parsons was John Parsons (1650-1728). He married Sarah Clarke (1659-1728) and a daughter was born in Northampton, Massachusetts on 5 July 1681 that they named after her paternal grandmother. Although she probably did not remember her grandfather Joseph, who died in 1683, young Mary probably would have known her grandmother well as she was 31 years old in 1712 when Mary (Bliss) Parsons passed away while living in Springfield.

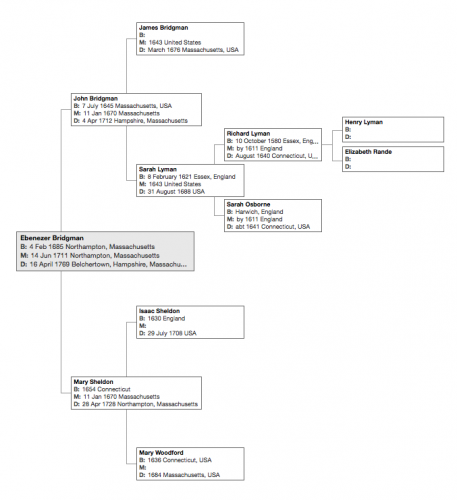

Meanwhile, Sarah (Lyman) Bridgman- the witch accuser- and her husband, James Bridgman, had only one son (and three daughters), out of eight children born to them who survived into adulthood. (This was part of the jealousy between Sarah and Mary (Bliss) Parsons- Mary had 9 children survive out of the 13 she had, 5 of them sons.) Their son John Bridgman chose Mary Sheldon (1654-1728) as his wife, and they had at least 11 children, possibly 14 per some sources; of these, Ebenezer Bridgman (1685-1760) is of interest to our story today.

Ebenezer Bridgman was born in Northampton too, still a very small hamlet on the frontier in February 1685. He likely saw young Mary Parsons on the street, in the fields, and in the meeting house. All the witch stories would probably have been heard by every family member, young or old. It would be so interesting to have a glimpse of their thoughts, and how they reconciled their business within the town, with neighbors, and possibly with members of the feuding family!

What parts did young Mary Parsons and Ebenezer Bridgman play in the local gossip that swirled through Northampton in 1702, when Mary (Bliss) Parsons was again called a witch? Young Peletiah Glover, another of Mary’s grandchildren, was told that his mother was half a witch and his grandmother a full witch who had killed several people. Did young Mary rush to protect her cousin? Did Ebenezer stay out of it, or try to shield Peletiah and the Parsons family from the mean words of some of the townspeople? There is no way to know the details of what happened 213 years ago, unfortunately.

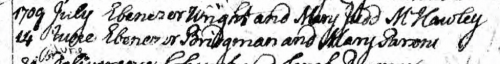

One day in 1709, however, the feud came to an end as the walls between families tumbled down:

Had the families known there was flirting going on instead of feuding?

Was there a big row when the young people stated their intentions?

(Although Puritans generally married at a slightly higher average age than the rest of the population, Mary was 27 and Ebenezer 24 at their nuptials- she was a bit older than usual, and was older than Ebenezer, too.)

Did everyone show up at the civil service for the marriage? Even Mary (Bliss) Parsons?

(Puritans did not believe in the church sanctifying a marriage- they felt it was a civil contract.)

Did the families pitch in together to help the newlyweds begin their new home?

All great questions to ponder, but sadly that is all we can do, as there has been nothing found to tell us more- no letters, diaries, etc. When telling the Mary (Bliss) Parsons witchcraft story, many historians do not even include the fact of a later unifying marriage between grandchildren of the feuding families.

Our ‘witch’ Mary would have bounced her grand-daughter Mary’s little babe Elizabeth Bridgman on her knee, and sung to the child the old lullabies Mary had heard as a child herself in England. Mary was in her mid-eighties by this time, and somewhat reduced in function and confused; her sons had needed to take over her financial affairs. Still, what thoughts might have gone through her mind, knowing that this precious great-granddaughter on her knee had the blood of the late Sarah (Lyman) Bridgman flowing through her rosy red cheeks? Were her thoughts of how the blood of the two families was now forever mixed, the family branches forever intertwined, after all the anguish of her own life? Did Mary think it was a sweet reconciliation, or did she gloat in the victory of her long life and so many children, grandchildren, and another great-grandchild to carry on her blood, while Sarah was already long gone, and had so few?

Elizabeth Bridgman was the first of four children to be born to Mary and Ebenezer Bridgman, but the only one who could have been held by her great-grandmother- Mary (Bliss) Parsons died in January of 1712. She would have been able to see her granddaughter big with a second child, however, as Joseph Bridgman was born two months later, in March. Mary (Parsons) Bridgman then carried on her own grandmother’s tradition of twins- Mary (Bliss) Parsons had at least one set of twins, likely two. The Bridgman twins Ebenezer and Mary were born 10 July 1714. Little Ebenezer would only live four months; we have no further information as to whether or not his sister Mary survived to adulthood.

Maybe the feud had been mellowing for quite some time, and the Bridgman family had softened. After all was said and done (in court and out), the new Bridgman family named two of their children after Mary (Parsons) Bridgman’s grandparents, the founders of the Parsons line in America: Joseph and Mary.

Notes, Sources, and References:

- See our four previous posts about the Mary (Bliss) Parsons slander and witchcraft trials in Northampton, Springfield, and Boston, Massachusetts by starting with, “No Ghoulies, No Ghosties, But a Witch? Yep.”

http://heritageramblings.net/2015/10/31/no-ghoulies-no-ghosties-but-a-witch-yep-part-1/ - Please see Part 3 of the above for the largest list of references for these posts.

- Mary (Bliss) Parsons- “The Witchcraft Trial-” http://ccbit.cs.umass.edu/parsons/hnmockup/witchcrafttrial.html

- Genealogy of the Bridgman family, descendants of James Bridgman,1636-1894, by Burt Nichols Bridgman and Joseph Clark Bridgman, 1894- https://archive.org/stream/genealogyofbridg00brid#page/n0/mode/2up

- I doubt that Puritans frequently went to plays- not an industrious activity, although as time went on in the Americas, the younger generations of the faith were not as devout as their parents. Even if they had not seen the play Romeo & Juliet, they may have read or heard of it. Wonder if Mary Parsons and Ebenezer Bridgman felt the connection or parallels, but with hopefully better results in mind than in the play?

Please contact us if you would like higher resolution images. Click to enlarge images.

We would love to read your thoughts and comments about this post (see form below), and thank you for your time! All comments are moderated, however, due to the high intelligence and persistence of spammers/hackers who really should be putting their smarts to use for the public good instead of spamming our little blog.