Military Monday: Henry Horn & the Battle of Trenton

McMurray Family, Horn Family (Click for Family Tree)

Two hundred thirty-nine years ago, in 1776, our McMurray ancestor Henry Horn was not having a good Christmas holiday.

The holiday had started out all right, comparatively- he and his fellow soldiers were warm and dry despite the raw, frigid, and stormy weather, with some of the men comfortably billeted in the homes of the locals in Trenton, New Jersey. Although far from home, the excitement of war was likely high in the young men- Henry was just 16 or 18- and a merry time was had by all. Christmas Eve was especially joyous- Germans celebrated Christmas Eve rather than the actual day. Our young Henry was really named Heinrich Horn and German, so likely celebrated in the same ways as his fellow soldiers.

If you are a follower of the blog, you may have read previous posts about Heinrich that reveal he was actually a Hessian soldier, not an American patriot in his early military years. Well-trained and very competent mercenaries, the Hessians were feared and loathed by the Americans, both military and civilian alike.

Heinrich Horn was a private in the 5th Company of the von Knyphausen Fusilier (light infantry) Regiment, which had been formed on 11 January 1776 in Ziegenhain, Germany. Technically they were, “German Auxiliaries” rather than “mercenaries,” as their ruler had sold their services as whole regiments to the British Crown.

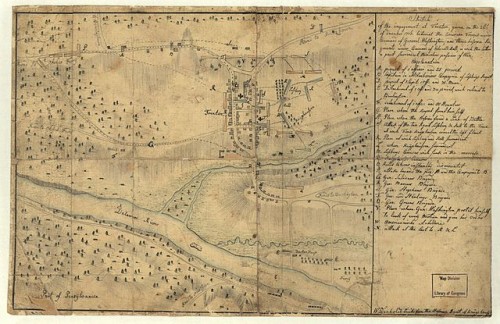

After crossing the ocean and participating in many battles against the American rebels, Henrich had arrived in the small New Jersey town of Trenton on December 14 with 2 other regiments. Trenton was to be the winter quarters of about 1,500 Hessians, 50 Hessian chasseurs (also known as Jägers, a rifle-armed light infantry similar to Army Rangers; Jäger means “hunter” in German, as does “chasseur” in French, the predominant language of the educated of the day) and a contingent of about 20 British Dragoons (infantry mounted on horses). Although the town of about 100 homes was not fortified, the Hessian brigade commander Colonel Johann Rall did not think it would be necessary- traditionally, troops did not move in such terrible winter weather, and he felt his forces so superior to those of the colonists that he denied many requests for fortification. Rall had been more interested in drinking and gathering spoils of war than military strategy. He was also was blinded by the contempt he had for the rebels, with their lack of organization and equipment, and their continued losses; Rall thought the War would be finished soon and easily.

The Americans had been attacking and harassing the Hessians for days. The Hessians and British in Trenton were exhausted from constant patrols and skirmishes at Trenton, and especially after coming off larger battles like White Plains and Ft. Washington. Many were sick or recovering from wounds. They slept in their uniforms with all their equipment. Each night, one regiment was on duty, ready to respond at a moment’s notice to any attack.

While the Hessian soldiers tried to get some rest in their ‘alert sleep’ in Trenton, George Washington and his ragtag group of Continentals- truly ‘ragtag’ as some had only rags for shoes or clothing- were crossing the Delaware to surprise the Hessians on December 25th. The men and artillery were across the Delaware by about 4 am on December 26th; they then had to march nine miles to Trenton in a driving nor’easter. The cold and exhausted American troops could be tracked by the blood in the snow from their bleeding feet and broken shoes, according to one contemporary account. But march they did.

Some of Trenton’s outermost Hessian guards had sheltered in a small guard house due to the severe weather and how quiet it was that night, with no American troops seen during any of the night’s patrols. The 24 Hessians inside tried to get a bit of rest, as they felt there would not be an attack in a frigid, blinding snowstorm. Once they relaxed their patrols, however, the Americans just happened to arrive near the outpost and attacked. Although they put up a good fight, the Americans were much more than just a raiding party, and the Hessians retreated to town, giving the alarm, “Der Feind!” (“The Enemy!”) The American forces attacked from the north and west, and large artillery began firing into the town from the Pennsylvania side of the Delaware River.

The alarm was sounded and Hessian drums awakened the men and sent the German regiments flying to form up and hold their ground. Col. Rall was still in bed, but his under officer was afraid to wake him. After sending men to support the pickets, the adjutant returned to headquarters, where his commander was hanging out his window, asking, “What’s the matter?” He was still “in his cups” from drinking the night before, and had not even heard the guns. (Legend has that all the German troops were sleeping off their celebration, but that is not true, since they had celebrated on the eve of the 24th and would have been sober by the morning of the 26th.) Col. Rall, an experienced military man, however, seemed disoriented and had difficulty forming a plan of defense. The Hessians mistakenly thought they were surrounded on both the left and right, but at that point, the Hessians actually still held the Assunpink Creek bridge, and could have escaped in that direction. (That likely would have changed American history.)

Heinrich’s Knyphausen Regiment formed up at the lower end of Queen Street, and prepared to meet the enemy. They were to be reserves as Rall’s Regiment and the von Lossberg Regiment marched up Queen (now Greene) Street. The American heavy artillery, however, along with rebel fire from houses along the street (and some fire by townspeople, including a woman who shot a Hessian captain), stopped Rall’s advance and killed half of the Hessians firing their own cannons, which were then taken by the Continentals. Col. Rall regrouped with his regiment and the von Lossberg Regiment in an apple orchard, and attempted to take the American artillery at the top of the hill north of town. George Washington, atop the hill, saw the advance, however, and was able to ward it off by swift troop movements.

Rall received more bad news- the guns of his own regiment had been taken in town. He turned his men toward the center of town to retake the guns and regain the all-important honor of his regiment. They bravely marched up King (now Warren) Street and were able to retake their cannon despite fire from all sides. The Americans then rushed to the guns with unbelievable determination, but Capt. William Washington (the cousin of George Washington) and Lt. James Monroe (our future U.S. President) of the Virginia Infantry were severely wounded. One of the sergeants took command of the Continentals and charged forward, and the last of the Hessians ran from their guns. The Americans then used the Hessian artillery to fire on the Hessian troops. In addition to the point-blank firing of cannon within the town, close-fighting had broken out throughout; civilians too were firing at the Hessians but also dying in the melee. Even seasoned military men commented afterward that it was one of the worst scenes of carnage they had ever seen.

The Hessians began to retreat, as the Americans had targeted and killed a number of their commanding officers, and they were confused as to tactics but knew the battle was all but lost. Additionally, the Hessian muskets were not firing due to the driving snow and sleet- some scholars estimate only 1 in 20 German guns fired on that fateful day. Many Hessians took refuge in a church or basement of houses in the town. The remainder retreated east to the orchard, with the Americans following. The Continental German regiment members called out to the Hessians in their native language to stack their arms and surrender, and one of Washington’s men rode up and offered them terms of surrender. The two Hessian regiments, those of Rall and von Lossberg, then lowered their colors and surrendered.

Heinrich Horn’s unit, the von Knyphausen Regiment, meanwhile, was still armed. They had marched to join up with Rall and his regiment at the beginning of the battle, but apparently in the chaos, an order was misunderstood: they marched southeast instead. Many of the weapons of Heinrich and his regiment would not fire either- it must have been a terrifying moment, even for such seasoned troops. Once they became aware of the poor prospects for the other two Hessian regiments, they moved toward the bridge at Assunpink Creek to escape to alarm British troops in nearby towns. There were 300 men and 2 guns in the regiment, but as they neared the bridge that had been held by the Hessians for most of the fight, they realized it was then in the hands of the Americans. The Americans had also surrounded the southern end of the town from that point.

Henrich’s commander, Major Friedrich von Dechow, turned the regiment and headed up the creek, looking for a place that was more narrow and could be forded more easily. Unfortunately the guns got bogged down in soft ground, and the troops lost time trying to free them. Americans followed closely behind and fired, and the Hessians were fired upon from the opposite bank of the creek.

Henrich and his comrades continued to march up the creek, looking for another place to ford. American soldiers jumped into the creek and attacked them, and American troops ran out of the town and attacked the regiment from the rear and both sides. Once they realized they were about to be surrounded, some of the Hessians jumped into the bitterly cold and icy creek to try to escape, but many were shot. About 50 Hessians of Heinrich’s regiment escaped via the creek and made it to Princeton, New Jersey, a distance of about 13 miles that took them 10 hours in icy temperatures with wet clothes, but our Heinrich Horn was not one of them. Major von Dechow was mortally wounded, plus was still suffering from wounds received in a previous battle. He recommended surrender, and was carried off the field. Although his officers did not want to surrender, when the Continental Army had them completely surrounded, there was no choice.

All hope was lost for a Hessian victory, and the von Knyphausen Fussiliers were the last Of Col. Rall’s Brigade to stack their arms as they were captured by the American rebels.

Our Heinrich Horn became an American POW on 26 December 1776.

The battle had only lasted about 45 minutes.

Heinrich and the other Germans were transported across the Delaware River by noon of that same day, and marched on to Philadelphia in the cold, snow, and ice. There were even German women and children, wives, children, and camp followers, who were captured by the Continental Army, although some had escaped early in the attack.

The Continental Army and militias did not have enough food or supplies for themselves, what’s less the large number of POWs they had captured. Our Heinrich Horn, like others of his regiment, must have been very cold, very tired, and very hungry, as well as despondent as to his situation. The Hessians had a reputation for treating their prisoners of war better than the British, but how would the Americans treat Heinrich and his companions? The once-merry Christmas holiday had become a nightmare for the almost 1000 Hessians troops captured that day.

As some of von Knyphausen’s Regiment had escaped earlier to the south, the Continentals pursued and captured 200 more men and their arms, ammunition, plus all of the victuals (food), clothing, bedding, and horses. These supplies were much needed by our armies, and may have made Heinrich’s capture a bit more tolerable if they were shared.

The Battle of Trenton was a turning point in the Revolutionary War. Until December 26, 1776, the rebels had not been very successful against the well-trained and well-equipped British and Hessian forces. Although Trenton was a small battle that strategically was not terribly significant, the fact that the Americans could defeat such an Army gave new life to the hope of freedom for the American colonies.

More to come about the life of Heinrich Horn.

[Editor’s Note: This post was edited 2 January 2016 with more detailed information.]

Notes, Sources, and References:

- Washington’s Crossing by David Hackett, 2004. Winner of the 2005 Pulitzer Prize for History, this tells the story of the crossing of the Delaware and the Battle of Trenton, mostly from the American point of view. This is an excellent book, and very well-written.

- The Hessians and the other German Auxiliaries of Great Britain in the Revolutionary War by Edward J. Lowell. Harper and Brothers Publishers, New York, 1884.

- AmericanRevolution.org: “The Hessians,” chapter VIII, an excellent read- http://www.americanrevolution.org/hessians/hess8.php

- Journal of the Fusilier Regiment v. Knyphausen From 1776 to 1783, possibly by Lt. Ritter? See http://freepages.military.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~amrevhessians/journal1.htm#navbar

- Henrich Horn http://freepages.military.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~amrevhessians/oh/hwardhorn.htm

- Hessians Remaining in America: http://freepages.military.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~amrevhessians/a/amhessians10.htm#navbar

- Wikipedia articles:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Trenton https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Order_of_battle_of_the_Battle_of_Trenton https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wilhelm_von_Knyphausen

Please contact us if you would like higher resolution images. Click to enlarge images.

We would love to read your thoughts and comments about this post (see form below), and thank you for your time! All comments are moderated, however, due to the high intelligence and persistence of spammers/hackers who really should be putting their smarts to use for the public good instead of spamming our little blog.